Memories of the Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia, August 21, 1968

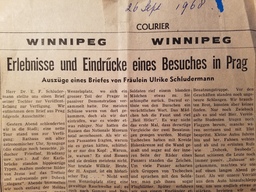

Going through my late father's belongings, I came across a newspaper clip from September 1968. He had published excerpts from my (German) letter to my parents in the “Canada Kurier”, a German newspaper in Winnipeg, Canada under the title: “Erlebnisse und Eindrücke eines Besuches in Prag”. (Experiences and Impressions of a visit to Prague)

Going through my late father's belongings, I came across a newspaper clip from September 1968. He had published excerpts from my (German) letter to my parents in the “Canada Kurier”, a German newspaper in Winnipeg, Canada under the title: “Erlebnisse und Eindrücke eines Besuches in Prag”. (Experiences and Impressions of a visit to Prague)

In the letter, I wrote how I was experiencing the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia on August 21, 1968, while in Prague. (I also found a few of my old photographs.) It was a scary situation.

As an Austrian immigrant to Canada, I still remembered the Russian occupation of Vienna after the War. And the Iron Curtain was still a real and psychological barrier for many Europeans at that time.

How I Got to Prague

A student from Canada, I was spending a couple of years as an exchange teacher for English in Freiburg, Germany. I was off for the summer and in my old Volkswagen Beetle, my American friend Harris and I drove from the Black Forest, through Bavaria into Austria.  On our way to Vienna, we decided to take a detour to Prague, Czechoslovakia, to see what the "Prague Spring" was actually like.

On our way to Vienna, we decided to take a detour to Prague, Czechoslovakia, to see what the "Prague Spring" was actually like.

On Monday August 19th, 1968, we arrived in Prague. We had heard that Alexander Dubcek, First secretary of the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, had started a reform program to establish "communism with a human face". The period of political liberalization got to be known as the "Prague Spring".

Dubcek had vehemently reassured Moscow that Czechoslovakia had no intention of leaving the Warsaw Pact (a political alliance between the Soviet Union and several Eastern European countries, established in May 1955).

We arrived in Prague late afternoon on that Monday, August 19th, 1968 and got accommodations at a student residence. There they rented rooms over the summer to tourists. [I don't know if that particular building still exists, but it was located about 4.5 km from the city center.]

The Published Excerpts From My Letter (Freely translated and edited)

Tuesday [August 20th], we toured the city: the Town Hall with its old astronomical clock, the Synagogue, the Castle, Kafka's house, the Charles Bridge.

On the bridge, hippies drew modern religious images and Dubcek slogans with chalk onto the sidewalks. Some of the young people were singing folk songs.

On the bridge, hippies drew modern religious images and Dubcek slogans with chalk onto the sidewalks. Some of the young people were singing folk songs.

In the evening, before returning to the student residence, we strolled by the Vltava river and chatted [in German] with one of the locals. He painted us a rosy picture of growing freedom in his country.

That night I dreamt of grey airplanes in my room but I didn't sleep badly. The next morning [Wednesday, August 21st], as I was in the women's washroom for a shower, a man rushed in and looked for his wife. He was Italian and kept shouting "russi, russi".

Later, at the reception, we were told that Soviet troops had unexpectedly entered the city with tanks and armored vehicles. It was to be a full fledged occupation.

Our first thought: Let's get out of here. We checked out of the student residence and tried to find gas for the car. But that seemed like a hopeless undertaking. We were told that all gas stations had been out fuel for hours. So we drove to the train station to call the Canadian and American embassies. But there we encountered Soviet tanks and troops.

We didn't want to leave the car on the street. For now, it seemed best to stay calm, get a place to stay and to wait and see. We drove back to the student residence and were lucky to get beds again for the night. We left the car there and walked back into the city center.

and were lucky to get beds again for the night. We left the car there and walked back into the city center.

In front of the grocery stores, we saw long lines of people hoping to stock up on food. An open truck drove down our street. On it people were waving flags. A bystander told us that they were chanting "long live Dubcek".

As we got closer to Wenceslas Square, we heard shots. But when we got there, things had calmed down. A large crowd of people had gathered on the square in passive demonstration.

A little farther on, we saw that the National Museum was riddled with bullets. When we asked a passerby why that building, he said: "Why, yes, why? They are Russians and they don't need a reason. Today, the 21st of August is a historic day for us".

Right then, a huge cloud of smoke rose up and we could smell rubber and gasoline. At the same time we heard the noise of automatic rifles and tank guns. Our passerby told us: "Oh, that's Radio Prague being blown up". Armored tanks thundered by. The soldiers on them shot periodically into the air. All around, people shouted and cursed, refusing to be intimidated.

Finding the Embassies

When things calmed down again, we took a side street and walked in the direction of the Canadian and American embassies. It seemed like a good idea to register with them. But the embassies weren't that close. And to get there, we had to cross the Vltava River.

The bridges were all guarded by soldiers in tanks. As pedestrians we could still move around freely, but traffic was at a standstill. We were afraid that once across the Vltava River, we would be cut off from our student residence.

Besides, a large part of the occupying forces were located around the Prague Castle, where Svoboda and Dubcek were being "isolated". The embassies were just around the corner from there. [Ludvic Svoboda was president of Czechoslovakia from 1968 to 1975. He achieved great popularity by resisting the Soviet Union's demands during and after its invasion of August 1968. (Brittanica)]

Still, we continued on and crossed the Vltava River over the Charles Bridge. Just like the local pedestrians, we zigzagged our way through the rows of armored vehicles that stood guard there.

A group of soldiers called something to a young woman. She swore back at them. They cursed in return. The woman lifted her fist and shouted. Swastikas had been chalked on some of the walls and we even saw one on the inner side of a tank wheel.

Local Czechs clustered around armored vehicles and spoke with the soldiers. Some even handed out flyers to the troops.

Local Czechs clustered around armored vehicles and spoke with the soldiers. Some even handed out flyers to the troops.

Later, we met an Englishman who told us the following: His girlfriend, who was Russian, had spoken with some of the soldiers. They told her that many of the occupying Soviet or Warsaw Pact soldiers were surprised to be in Prague and not in Poland. Others only knew that they were fighting a "counter revolution". Still others only shook their head and said: "We don't know anything, we only follow orders."

We finally reached both the American and the Canadian embassies and left our names there. By now it was three in the afternoon and it seemed wise to return to the student residence. After all, we had a long walk in front of us and who knew what problems we would still encounter. Luckily, going back over the Charles Bridge went without a hitch.

But now all bridges were being guarded even more heavily. On all larger streets stood rows of armored vehicles. On the public squares you could see an increased number of soldiers, each with an automatic rifle. It seemed to me, though, that their uniforms looked a little ragged and not really adequate for an occupying force.

Food and Gasoline

The lines in front of the grocery stores had not gotten shorter. We needed bread, but couldn't find any. All we could get was a package of crackers and beer.

A few people carrying flags were still walking around or driving back and forth in small cars. Some of the flags were torn and spattered with blood. We heard shouts of "Dubcek, Svoboda". But in general, people were passive. Once we arrived at the student residence, we knew we were in for a long evening.

Upstairs while we ate, we discussed our "gas problem". We knew we had enough gas for about 40 km. But the nearest border crossing was at Gmünd into Austria, and that was about 175 km away. Other border crossings were even farther and we feared running into a blockade or being forced to take detours.

An East German man from Leipzig explained to us how utterly hopeless the situation was. But he mentioned that the only station that still sold gas was only about a kilometer away. We hopped into the car and drove there. A long line and a long wait, just to get 10 liters of gas. It was not enough to reach the border, but it was something.

Information and Rumors

In the hall of the student residence, the radio brought the news, always the same bad news. Everything seems so unreal. Waking up in the morning of Thursday, August 22 we heard no airplanes, only the constant noise of Soviet trucks bringing supplies, cannons, and new troops.

In the women's washroom - the place where we got our first information of the day - one rumor had it that it was impossible to leave the country by car. Nor were there any trains back to the east block countries or to the west.

There were also other rumors:

• All border crossings were blocked, except the crossing at Gmünd to Austria;

• or, the best way to leave was via Hungary;

• or, the only crossing that was open was the one at Waidhaus in the direction of Pilsen;

• or, the Vtlava River was blocked everywhere, no chance to cross it;

• or, some tourists had tried to leave the country and were sent back, etc.

People like us were beginning to feel a little desperate. It was impossible to call either of our embassies, all telephone connections were cut off. A man who spoke both Czech and German said that the Austrian embassy advised all tourists to leave the country as soon as they could. We knew we had to act.

Being Lucky

We lined up once more at the gas station. With an extra note, we bribed the attendant to go over the usual ration and fill our tank. An American student, who had no hope of leaving Prague by train, asked to join us. Together with him, we discussed how to proceed: either via Budweis to Freistadt or to Gmünd, depending on the information we could get.

With some difficulty we got through the city by car. We had to avoid the heavily guarded areas. And even though locals kindly tried to help us, they were too upset to think clearly. Outside of the cities, we saw confusing road signs. Some of them were obviously turned the wrong way and pointed north to Moskau. Others had different place names written over them.

In the villages along the road people gave us fliers. In one town they tossed flowers to us as we drove by. In many places, the names Dubcek and Svoboda were written in chalk on the road. About an hour before the border, we came across another gas station and could fill up again.

A woman said we definitely needed to drive to the Gmünd border crossing. On our way there we caught up twice to a convoy of tanks. It was easy to recognize the Soviet tanks. They had a thick white stripe on their frame.

At the border, there was only a normal line of cars waiting to cross. We didn't see any Soviet vehicles. Later we heard that Gmünd really had been the only open border crossing at that time. A man we talked to had first tried crossing at three other places and but was turned back by Soviet soldiers.

We also heard that Soviet tanks were supposed to arrive at Budweis at 5 o'clock. Half of them would continue on in the direction of Gmünd to close the border there. I guess we'd been really lucky. In Viennese, you'd say we had "a Masl".

Postscript: I only learned later how lucky we indeed had been: There were over 100 people killed during the invasion. We never saw any of the battles, especially those around the radio station (about which we only heard rumors and sporadic gunfire).

If you're interested to learn more about the Prague Spring or Czechoslovakia, I'd suggest Mary Heimann's book "Czechoslovakia: The State That Failed". We are currently reading it in preparation for our visit to Prague later this year. It provides an excellent account of the birth of the multinational state of Czechoslovakia in 1918, its tribulations before and during the Hitler years, the period of Communist rule, and its dissolution on December 31, 1992.

Bio: Ulrike Rettig is the co-founder of GamesforLanguage.com. She's a lifelong language learner, growing up in Austria, the Netherlands, and Canada. You can follow her on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and leave any comments right here below! (And if you'd like to read the original German version, just send us a note to contact.)